A Mystery of American Indian Family Heritage

Sauk Chief Blackhawk

Like many American families, one of our common legends was that our heritage is part Cherokee. I took this to be true for a long time, until a closer look at the ancestry record, brought this into question. I still believe the Aemrican Indian part and believe I have some evidence to support it, but it’s the Cherokee specific part that doesn’t quite seem to fit the factual evidence.

My paternal grandfather was born in Indian Territory (eastern Oklahoma). This is the region where the Cherokee and Choctaw migrated on the Trail of Tears following the Indian removal act of 1830, passed under President Andrew Jackson. As a group, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, and Seminole tribes were systematically forced to leave the southeast and head west, first to what is now Arkansas and then to Oklahoma. The Cherokee were the last to be forced out in 1838. In the family records the ancestor who would have been the Indian connection was my grandfather’s grandmother.

But on closer examination into genealogical and historical records, though my grandfather was born in the Oklahoma Indian Territory, his parents had moved there from western Illinois where his mother was born. His father, at the time of my grandfather’s birth, seems to have been working on a spur of what became the Frisco Railroad which was being built to Afton.

The ancestor who would have been the “full blooded” native to whom we traced our Indian ancestry was according to records, born in 1832 or 1833 in western Illinois. The indian migrations from the south from the Removal Act had begun by 1831, but mostly to the area of Arkansas, so the likelihood that they would have reached as far north as the Illinois River by that time seems unlikely. Further complicating the Indian heritage legend was the discovery in fairly reliable genealogy records that my great-great grandmother, the individual who would have been the Indian, had a family heritage in official records as being “white” with parentage going back generations into Maryland. The whole Cherokee ancestry myth seemed to be on the brink of falling to pieces. Except for a piece of evidence recently found and some other facts which intriguingly add to the picture and the mystery. A family photograph of my grandfather as a boy taken with his brothers and sisters, mother and father in a full family portrait. The photograph offers two tantalizing questions.

The fact of the photograph itself. Aside from the notations of the first names of the family members, there is no notation of the time or place or occasion of its being taken. However, my grandfather was born in 1887 and appears in the photograph (second from the left) to be about 12 or 13. This would place the photograph right around 1900, leading to the conclusion that it is indeed exactly 1990. That to mark the turn-of-the-century, it was thought to go out and take a formal family portrait to commemorate the historical moment.

The other tantalizing and evidential nature of the photograph is the faces of the family, Among them, there is a distinct and clear difference of a racial mix. The father in the picture is purely European and a Germanic (that family branch was German going back several generations), while the mother bears a mix herself, and becomes even clearer in the mix of the children, especially the younger children on the left. The older children were from an earlier marriage. So, with visual evidence, the idea of a Native American genetic connection seems quite clear.

But why doesn’t the documentary evidence support it? I have a theory which may or may not bear out.

Black Hawk War

In 1832, the western Illinois territory where German immigrants had migrated from Pennsylvania, (West) Virginia and Ohio, was wracked by the Blackhawk War. A tribe of Sauk and Kickapoo Indians from an area is what is now Iowa, crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois following a leader named Chief Black Hawk (pictured above with his son Whirling Thunder), hoping to peacefully reclaim lands ceded in an 1804 Treaty. The “war” was really a series of skirmishes, attacks and reprisals, taking place through western Illinois into Wisconsin. The Black Hawk War in most noted historically in the military service of future United States President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln commanded a regiment of militia volunteers, though he never participated in any actual conflict.

The Black Hawk War was, in the scheme of history, a fairly minor conflict, but with wide ranging consequences. Other figures who played a military role went on to became major figures in the Civil War and American History: Winfield Scott, Jefferson Davis and future U.S. President Zachary Taylor. The conflict of the war with its reported “massacres” also fueled the already underway Indian Removal Program under Andrew Jackson, leading inevitably to the “Trail of Tears” and other removal deprivations.

But I have a suspicion that a small figure also left a mark on a personal family history. My theory is that my maternal great-great grandmother may have been a war orphan, taken in as an infant by a German immigrant family, who would have given her a European name, brought her up as a daughter and would have told census takers and anyone else who asked, that she was white, melting into the fabric of the American Sampler.

Another clue as yet unresolved, has my grandfather’s grandmother listed in census records for over 50 years, moving from Illinois to southeast Kansas, in an area said to be populated with Osage Indians and Cherokee and reported with many “Euro-Americans with Osage or Cherokee wives”. Perhaps this historical reference refers to my great-great-grandparents. Or perhaps not.

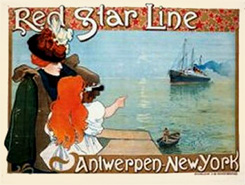

Beginning September 28th, 2013 the new Red Star Line Museum in the historic harbour warehouses of the Red Star Line shipping company in Antwerp opens to the public. This experiential museum tells the story of the millions of immigrants who travelled from Antwerp to the United States and Canada on board the ocean liners of the Red Star in search of a better life.

Beginning September 28th, 2013 the new Red Star Line Museum in the historic harbour warehouses of the Red Star Line shipping company in Antwerp opens to the public. This experiential museum tells the story of the millions of immigrants who travelled from Antwerp to the United States and Canada on board the ocean liners of the Red Star in search of a better life.